Undergraduate Programs:

School of Health and Life Sciences

School of Business and Management

Postgraduate Program:

Professional Program:

Pharmacist Professional (Apoteker)

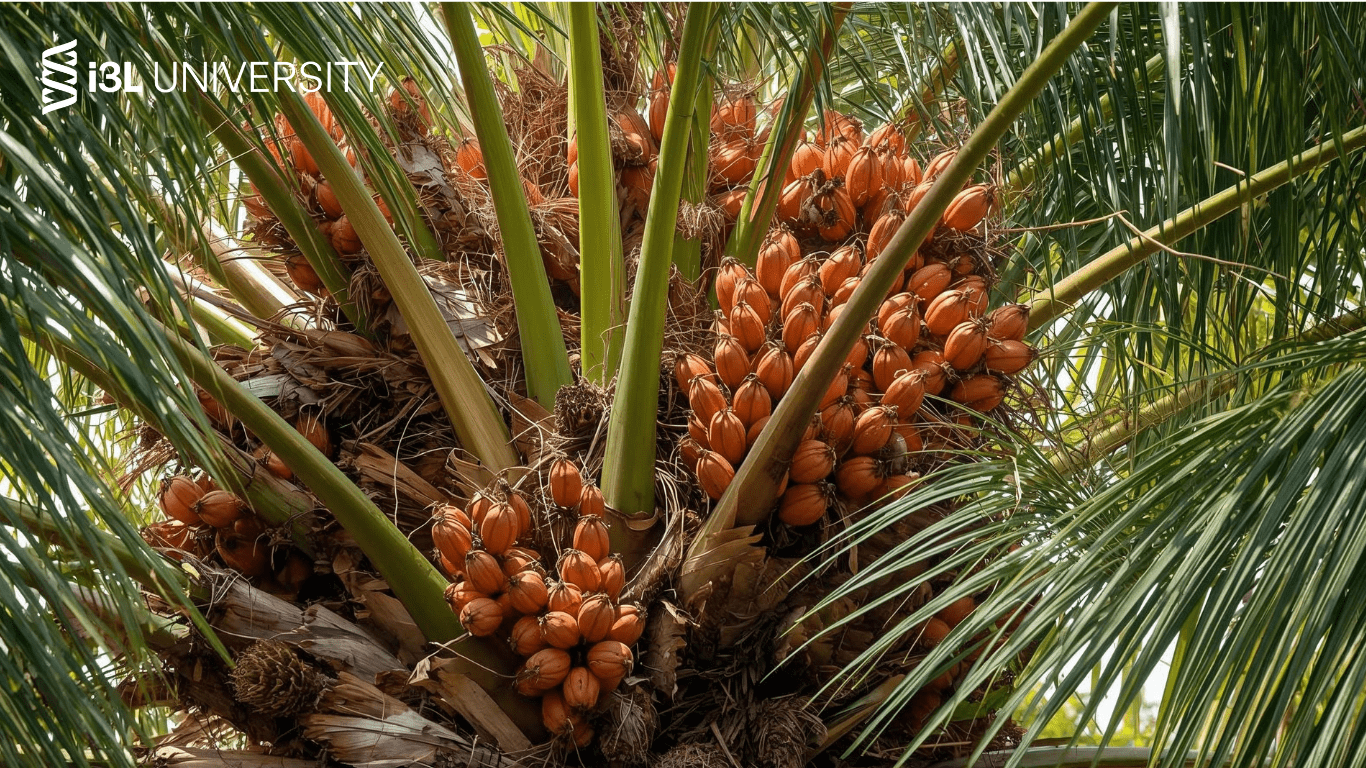

A Tree Crop, Not a Forest: Why Oil Palm Plantations Don’t Deliver the Same Climate and Flood Benefits

Jakarta, 05 December 2025 – In late 2024, the statement made by Indonesia’s current president regarding oil palm—that it is a tree that absorbs CO2 and should not be considered a contributor to climate change—has gained renewed attention. This comes in the wake of extreme rainfall and a cyclone in Sumatra and Aceh, which have caused floods and landslides. These disasters renewed debate about land use for monoculture plantations (e.g. oil palm plantations) and how the trees in natural forests are not just merely trees.

Some politicians argue that because oil palm is a tree, it should provide similar environmental functions to forests as they sequester CO₂. Botanical and ecological science, however, draws an important distinction: plantations may sequester CO₂, but they do not replicate the wider benefits of a tropical forest ecosystem, such as biodiversity support, complex habitat structure, soil protection, and water regulation. From a scientific perspective, it’s essential to base comparisons on established ecological classifications and measured ecosystem functions, rather than on whether the vegetation is simply “made of trees.”

The argument is that all living things that have a leaf structure will have similar functions. However, the role of living things in a community is not solely determined by one of its body parts; it is the whole entity of the organism.

A key claim in the debate is that oil palm is a “tree,” so plantations should contribute to climate solutions in the same way forests do. The science is more specific: what matters is total ecosystem carbon, i.e. carbon stored aboveground, belowground, and especially in soils, not simply whether the dominant plant has a trunk.

A natural rainforest is not just “a lot of trees.” It is a multi-species, multi-layered ecosystem—emergent trees, closed canopy, sub-canopy, understory, and a rich forest floor which supports thousands of interacting species. By contrast, an oil palm plantation is typically a monoculture crop system, dominated by a single species planted at uniform spacing and often managed to reduce understory vegetation.

Biodiversity loss: When rainforest is converted into an oil palm monoculture, the landscape usually loses much of its habitat complexity, food resources, and nesting sites. Across many studies and taxa, species richness and abundance can drop severely, putting additional pressure on forest-dependent wildlife (including iconic endangered species such as orangutans and tigers in parts of Southeast Asia).

The same features that reduce biodiversity can also weaken the landscape’s ability to buffer heavy rainfall.

At the end of the day, this debate should not be won by redefining what a forest is. It should be won by reducing real environmental impacts, such as carbon loss, biodiversity collapse, soil degradation, and flood risk through better science, improved land management, and enhanced accountability.

This is where i3L University’s Biotechnology Study Program can make a practical contribution. Through the Sustainable Biotechnology stream, students are trained to tackle sustainability not as a slogan, but as a measurable set of problems that demand evidence-based solutions.

If national fuel policies increase demand for biodiesel blends (such as B50), the sustainability question becomes urgent: How can production scale without pushing further land conversion? One realistic pathway is to improve resource efficiency by utilising existing resources—especially oil palm waste streams, such as empty fruit bunches (EFB), palm kernel cake, and palm oil mill effluent (POME).

At i3L, students learn core bioprocessing skills, including fermentation, anaerobic digestion, enzyme-based conversion, downstream processing, and basic process design, which can be applied to converting these wastes into biogas, bioethanol, or other bio-based products.

Contribution in practice: Graduates can support industry projects that reduce emissions and waste burdens per ton of palm oil, helping companies increase output and energy yield without automatically expanding plantation areas.

EU sustainability expectations are evidence-based: companies need to demonstrate traceability and verifiable environmental performance, not just make claims. i3L’s environmental biotechnology training equips students with practical skills in sampling, basic laboratory analysis, and data handling that support sustainability monitoring in plantations and mills.

Contribution in practice: as entry-level staff or assistants to company sustainability teams/consultants, graduates can help with water and effluent monitoring (e.g., key wastewater parameters from POME treatment), soil health indicators, and structured documentation for audits—strengthening Environmental, Social, and Governance implementation and making compliance efforts more credible and measurable.

Oil palm is a tree crop, but a plantation is not a rainforest ecosystem. The responsible response is not to blur definitions, but to invest in science and talent that reduce the real drivers of risk: emissions, degraded soils, and disrupted hydrology. If Indonesia wants palm oil to remain globally competitive while protecting landscapes and communities, the most defensible path forward is innovation, verification, and restoration; exactly the skillset that biotechnology education can help build.

FITZHERBERT, E., STRUEBIG, M., MOREL, A., DANIELSEN, F., BRUHL, C., DONALD, P., & PHALAN, B. (2008). How will oil palm expansion affect biodiversity? Trends in Ecology & Evolution, 23(10), 538–545. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2008.06.012

Oil palm refers to the organism, the plant, palm oil is the commodity, and oil palm plantation refers to the use of land to grow the plant.

Yes, it is a tree. But in strict botanical terms, experts categorise them as a non-woody plant, a monocot, a palm. It lacks the carbon storage capacity and biodiversity support of a natural forest ecosystem.

No, compared to natural forests, they often increase flood risks. While industry proponents argue that oil palm canopies cover the soil, scientific consensus and recent data from the late 2024/2025 Sumatra floods indicate otherwise:

i3L University’s Biotechnology Study Program focuses on scientific solutions rather than semantic ones. Through research on Bioprocessing Technology to convert palm waste into energy and development of better traits plants through Genetically Modified Organisms (GMOs), i3L aims to make the industry sustainable without expanding into new forest lands.

Indonesia International Institute for Life Sciences (i3L) is a globally connected research and education institution that impacts society through science and innovation. The Biotechnology program at i3L is interdisciplinary education, where innovations are directed to enhance quality of life via the production of valuable products from Indonesian biodiversity. This program offers a broad content, which nurtures well-rounded graduates to become leaders in various fields of biotechnology.

Undergraduate Programs:

School of Health and Life Sciences

School of Business and Management

Postgraduate Program:

Professional Program:

Pharmacist Professional (Apoteker)

Undergraduate Programs:

School of Life Sciences

School of Business

Postgraduate Program:

Professional Program: